Introduction

This is part 1 of a 3-part bit on voting and elections.

First of all, a disclaimer: I’m not a political scientist, I am not an expert on the constitution or any other relevant field. I’m commenting here just as an individual. These ideas are either my own, or ideas that I’ve come across and like. This is very much an “armchair expert” situation. That being said, I’d like to share my thoughts on the electoral process in the United States, and an idea for alternatives.

A YouTuber/podcaster who goes by CGP Grey has done a series of five short videos, titled Politics in the Animal Kingdom that I think does a fantastic job explaining methods of voting and some problems that arise with some of them. In this post, I’ll be summarizing some of these voting methods, but I highly recommend watching those videos.

Initially this may seem odd to some people. Voting is voting, right? You cast your ballot for who you support, and then whoever gets the most votes wins. While that is one way of voting, it is not the only way (and actually has some significant drawbacks).

Plurality voting

The current approach used in most races in the United States uses a plurality system (sometimes called a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system) of voting. Everyone votes for a single candidate, and to determine the winner we just look at who got the most votes. They win even if they didn’t get a majority. In case that seems odd, it’s because a majority would be over 50% of votes, while a plurality just means a larger percentage than any other individual candidate.

For example, in a race with 3 candidate (Calvin, Hobbes, and Suzie), suppose Calvin gets 40% of the vote, Hobbes gets 35%, and Suzie gets 25%. Calvin would win by plurality, even though he did not get a majority. Even if all of Suzie’s voters preferred Hobbes to Calvin (so that, if Suzie was not in the race, Hobbes would get 60% - a majority), Calvin still wins.

This is how virtually every senator and representative in the country is selected (Maine was the first to use a different method in the 2018 election, and Alaska approved a different method in the 2020 election). There are several problems with plurality voting.

Some Problems with plurality

No majority

First, as demonstrated in the little example above, a plurality system does not guarantee that the winner gets a majority of votes, or is the most broadly preferred candidate (which casts a shadow on the concept of “majority rule”).

Duopoly

Second, a plurality system tends to lead to a 2-party system, which we’ve seen for a long time now. If you don’t like the 2-party system, then you should hate a FPTP system of voting.

The example hinted at this: If all of Suzie’s supporters would have preferred Hobbes to Calvin, then eventually they will grow tired of losing elections to their least-favorite candidate. Instead of voting for their favorite, they’ll vote a candidate that is still acceptable to them, but more likely to win. This is known as Duverger’s law, and it is how we wind up with two “big tent” parties, and why third parties are all but invisible: Since they are not likely to win, people who agree with the third party will instead vote for one of the two major-party candidates, making it even less likely for the third party to win, which leads even more supporters to vote for the main parties.

To be clear: I do not subscribe to the notion that a third party vote is a “wasted” vote. However, I think that it needs to be understood as a protest vote - an indication that there are engaged voters who are unsatisfied with both main parties - rather than a real attempt to elect a candidate into office.

Gerrymandering

A third problem with plurality voting is the prospect of gerrymandering. I don’t think that gerrymandering is technically limited to plurality voting, but plurality voting in single-member districts (FPTP) is particularly susceptible to it.

To back up slightly: While it may seem like there is “an election,” in reality it’s more like 534 separate elections: 1 president, 100 senators, and 435 house representatives. Well, sort of. Only 1/3 of the senate is up for election at any given election, but that doesn’t really matter for this discussion.

Senators are elected from a state-wide vote, but house representatives are elected from a district within a state. These districts are not fixed things. Within a state they are supposed to be approximately equal population, and so as the population changes, the districts may change. Gerrymandering, also called “cracking and packing”, is the tactic by which these districts are drawn to favor one part or the other. The basic idea is that you “crack” the opposing party’s support across many districts, to dilute its effect. If it’s impossible to fully achieve that, you “pack” as many of the opposing party into a single district as possible, so that they are guaranteed to win that district, but with many of their votes concentrated there, they are weaker in multiple other districts.

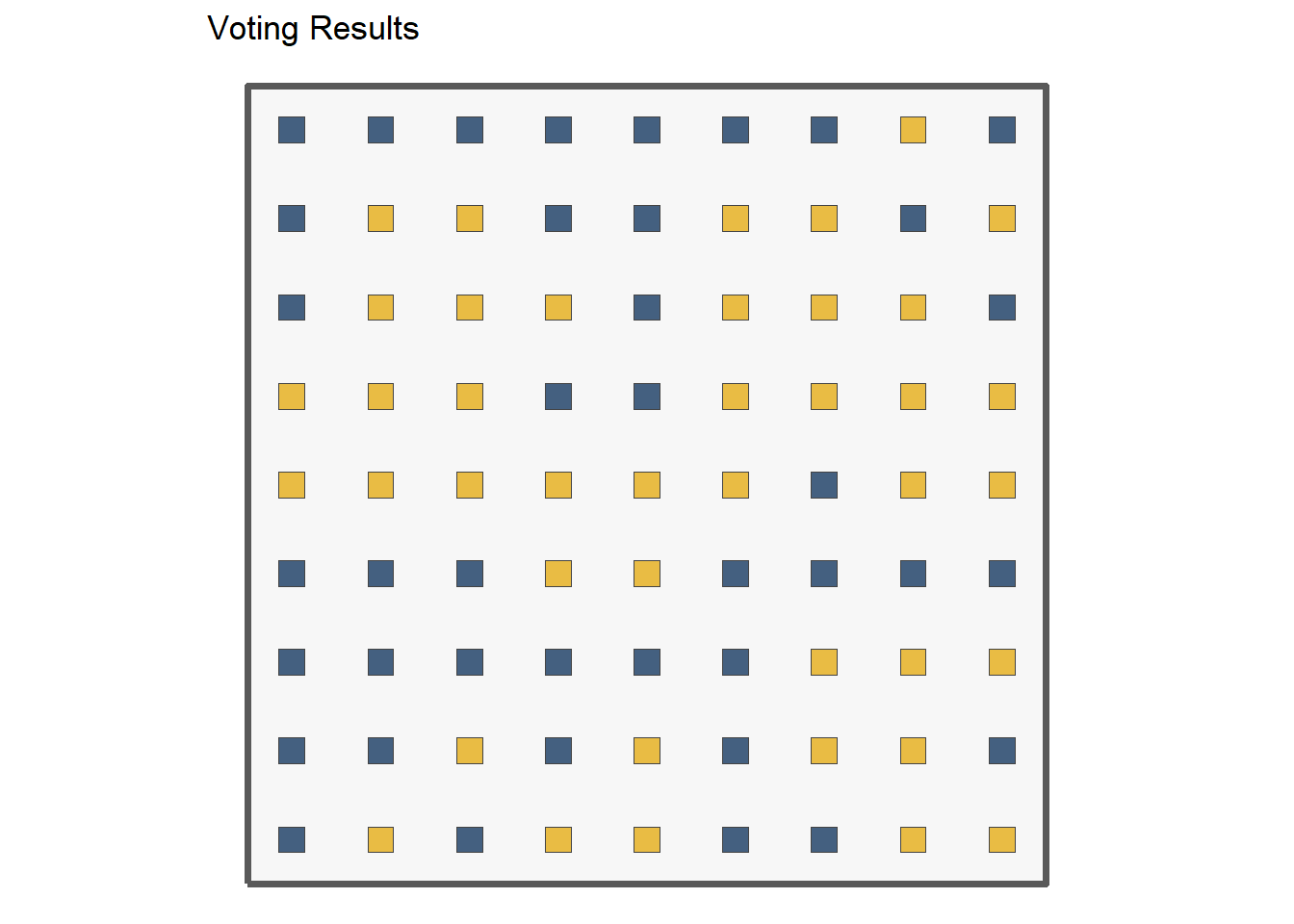

Consider a square state with 81 voters who need to be divvied up into 9 districts, each with 9 voters. These voters vote for one of two parties, Blue or Gold. In the figure below, I’ve randomly distributed the votes around the state. The vote tallies are as evenly divided as possible: 40 for Blue, and 41 for Gold.

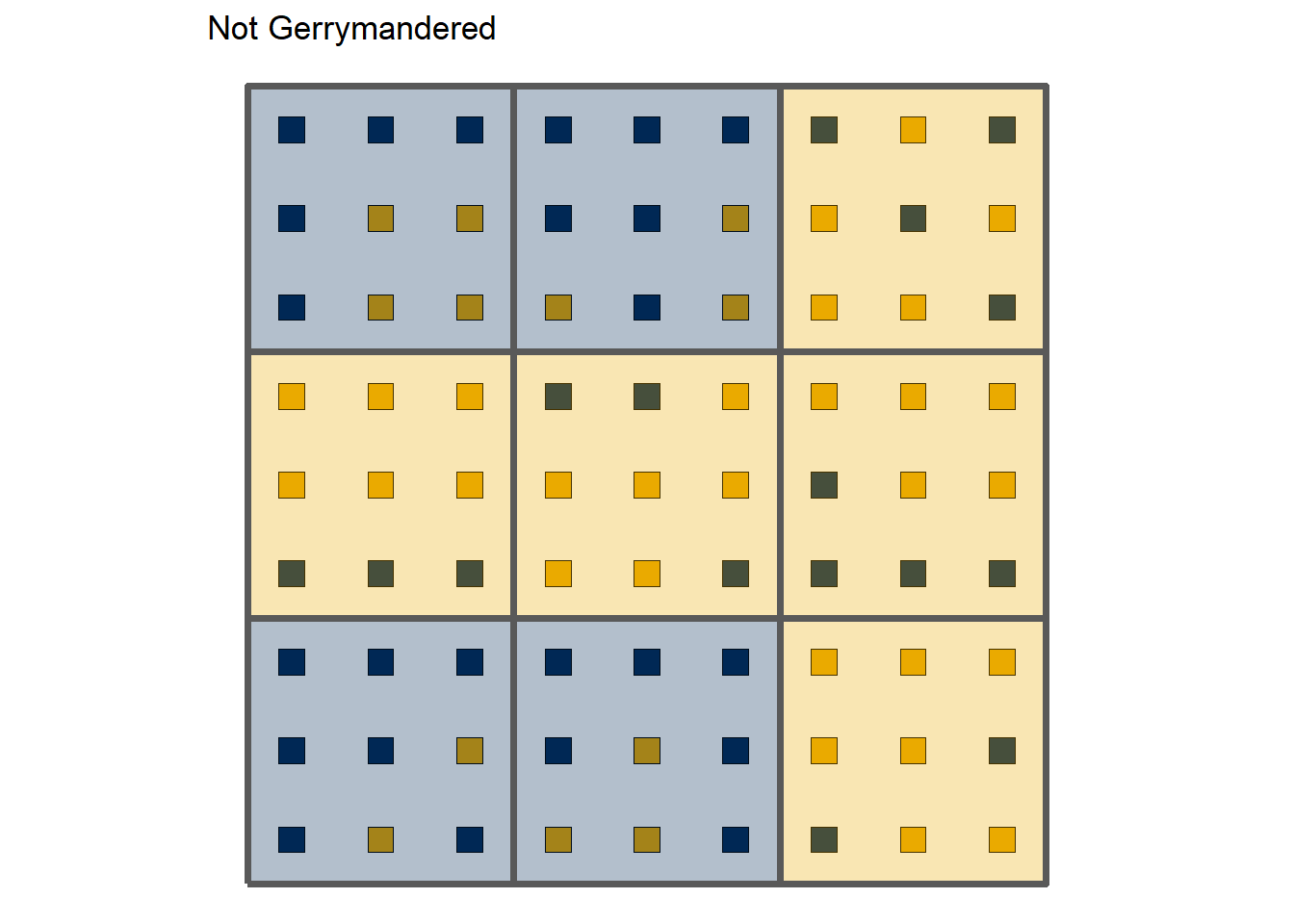

Now, we need to draw districts. With no knowledge of this fictional state, we might just draw 9 boxes, no? That would be one approach. It turns out that doing so, the parties each win roughly half of the districts, which seems more or less fair (and, since I distributed the votes randomly, should be expected).

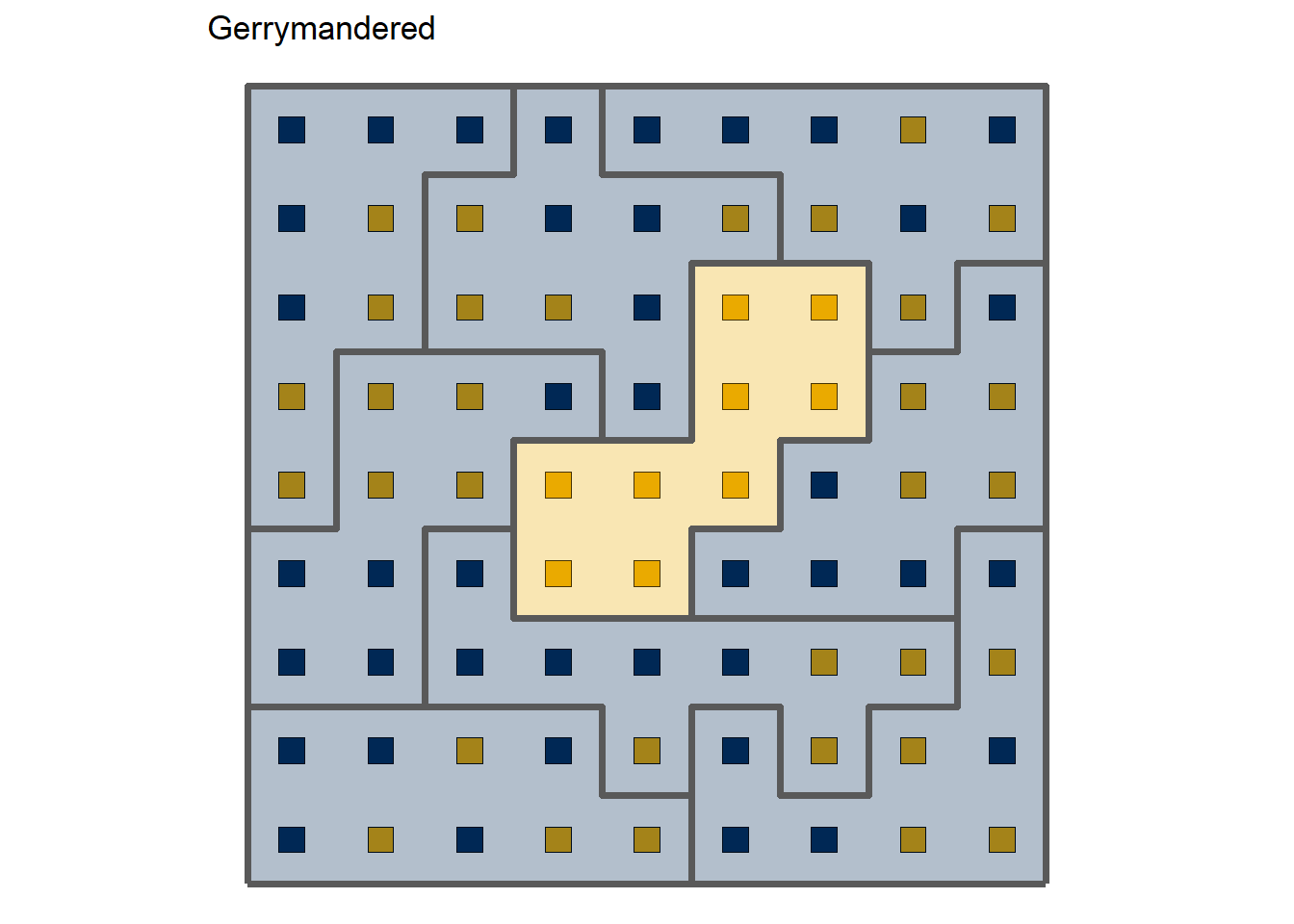

However, say the Blue party gets to draw the districts, and they decide to gerrymander to give themselves an advantage. Their target should be to create as many districts with 5 Blue votes as possible.

How might they do that? Well, I just came up with some gerrymandered lines myself. I noticed a block of Gold votes that was all connected, so I put them ALL into a single district (“packing”), giving Gold a guarantee to win that district. However, that siphons off a lot of the Gold votes, allowing me to spread the rest of them out so that Blue gets all of the remaining districts.

So even though they only received roughly (and actually just under) 50% of the vote, Blue was able to claim nearly all but one district, for roughly 90% of the representation. That seems wildly unfair. And I’m not even an expert at this! I just looked at this map for a little bit and drew some lines.

Summary

So, voting systems that can be gerrymandered have this big flaw. We’d prefer a system that is immune to gerrymandering. You can continue reading my take on some alternative methods in Voting Methods Part 2.